The UK has witnessed a gin boom in recent years, now there are signs that it might go global

Credit to New Tork times and Independent.

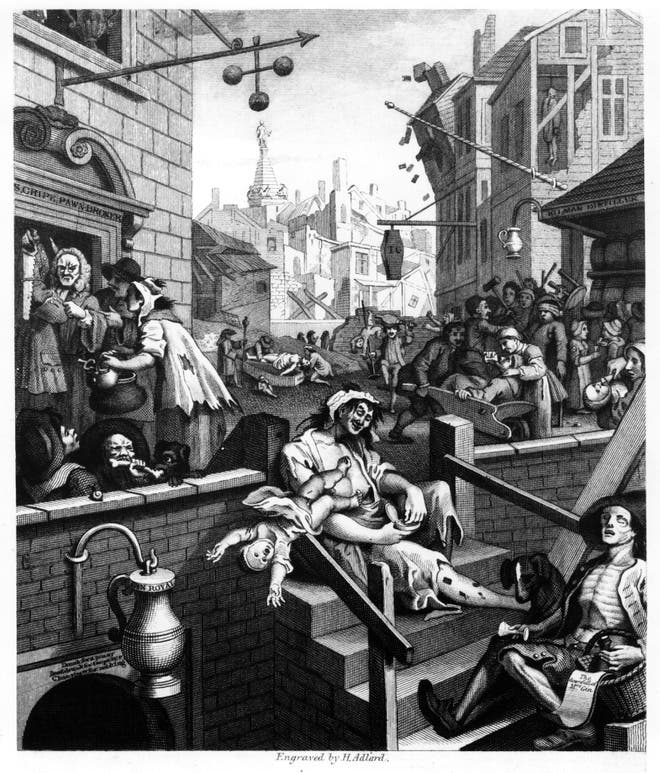

Ever since European apothecaries began distilling gin and selling it as a cure-all in the 16th century, the juniper-flavoured liquor has been revered as a medicine, vilified for fuelling public disorder and consumed in a multitude of every-season cocktails.

Now, it is stirring up a specialised tourist trade in London, thanks in part to entrepreneurial bottling and branding.

After surging for a decade, gin sales in Britain reached nearly £2bn last autumn. This compared with £1.26bn for the same period in 2017, according to the Wine and Spirit Trade Association. Drinkers of pink and flavoured versions have helped make it the country’s second-most-popular spirit. This is ahead of whisky and behind only vodka, the group says.

Gin has become so popular in Britain that the Office for National Statistics (ONS) added it back to the basket of goods it uses to measure inflation after a 13-year absence.

Many of the newer products share the flavour of juniper, but others vary widely from traditional dry gin, which, by European law, must be distilled from natural plant materials and have a minimum of 37.5 per cent alcohol by volume.

The revival has spawned gin-flavoured marmalade and gin-scented candles, prompting fears of overkill among some British producers. As a result, they are seeking new growth overseas.

The birth of a new boom

Sam Galsworthy and Fairfax Hall, childhood friends from Britain, were working in the beverage industry in the United States in the early 2000s and watching microbreweries and craft distilleries multiply around them.

They set about starting a gin distillery in west London in 2007, but were quickly stymied by bureaucratic rules stretching back more than 250 years.

In 1751, British officials, worried that too many people were succumbing to so-called mother’s ruin, passed the Gin Act to stamp out small-scale and home production by limiting gin-making to stills with a capacity of at least 1,800l.

Galsworthy and Hall lobbied the government to ease the restriction. In 2009, their company, Sipsmith, was granted a license to produce gin. The move opened the door for other small distilleries.

Gin-making has exploded in Britain since then. The number of distilleries grew to 419 in 2018 from 113 in 2009, according to the ONS.

The distilleries have become popular tourist destinations. Sipsmith says it gets about 25,000 visitors a year. Taste-testers like that – those buying the experience as well as the gin – have helped fuel the growth in sales.

“It’s part of a food culture that probably didn’t exist in the UK 20 years ago,” says Miles Beale, chief executive of Britain’s Wine and Spirit Trade Association. “People are drinking less, but they’re more interested in what they’re drinking. They will spend money on it.”

The benefit of a good back story

Ian Puddick was renovating the London building that housed his plumbing business in 2013 when he discovered that it was once home to a bakery where illicit gin was made.

He tracked down the owners’ descendants, and although they didn’t give him a recipe, they identified several ingredients. With that and some guesswork, he came up with Old Bakery Gin, which is now sold at Harrods and Fortnum & Mason.

Puddick’s tale is one of many origin stories whetting the appetite of the new generation of gin connoisseurs. Oscar Dodd, a Fortnum & Mason buyer, says shoppers often wanted to learn more about the provenance or ingredients of their purchases.

“They’re nearly all looking for something new and exciting,” he says. “There’s a social currency with gin. You want to introduce your friends.”

Still, the proliferation of new gin is a challenge for relative neophytes like Puddick.

“That brand loyalty, getting people to choose your brand above others, is definitely getting tougher,” he says.

A heavyweight sticks to the basics

Beefeater, a London staple since the 1800s, is sticking to basics even as rivals keep sprouting up. If the rise of sloe gin and snow globes with gin bottles leads to consumer fatigue, the company wants to make sure its product remains the main ingredient in gin-based cocktails.

“Gin is designed to work in many different directions,” Desmond Payne, Beefeater’s master distiller, says. “Very few people drink gin on its own. Gin should have the ability to be versatile and work in different directions.”

Beefeater welcomes the industry’s growth and has even produced some limited editions of new blends. Still, Payne is wary of making something too different from the product that the company sells 2.9 million 9-litre cases of a year.

The risk with some of the experimental gins that have emerged, Payne says, is that “they’re too much about one particular thing”, limiting their ability to work well in all types of cocktails.

‘It’s both grown-up and hipster’

Galsworthy of Sipsmith expects the gin boom to stall at some point. “Make no bones about it,” he says, “the proliferation of it endangers the category in of itself”.

He and other distillers are looking beyond Britain for new customers. Sometimes getting snapped up by big alcohol companies that hope to capitalise on a global gin market that, according to the research firm Euromonitor, grew to about £12bn in 2017 from £8bn in 2007.

In 2016, Sipsmith was acquired by Beam Suntory, which has also acquired Japanese and Spanish gins. Diageo, which owns popular brands like Gordon’s and Tanqueray, added a Japanese-inspired gin to its offering.

Smaller entrants from other parts of the world are also getting into the market.

Dragon’s Blood Gin has just started making gin in a custom-built distillery in Inner Mongolia, China. Peddlers Gin, a Shanghai brand, recently signed an international distribution deal. New distilleries are popping up from Australia to Liechtenstein to the United States, says Nicholas Cook, director of the Gin Guild in Britain.

Gin’s appeal, he says, is that “it’s both grown-up and hipster at the same time”.

Joseph Judd, who helped found Peddlers Gin, says even as the company sought to increase its global reach, especially in Asia, it was hewing to the liquor’s European heritage.

“I think it would be difficult to come with purely Chinese ingredients and disregard the British perspective,” Judd says. “With gin, you have to respect the process and the history.”

© New York Times

Privacy Policy - your information will never be shared

Privacy Policy - your information will never be shared